Getting it right from the start: Intentional literacy in the early years

Literacy in the early years isn’t about rushing children to read and write before they’re ready. It’s about laying thoughtful, intentional foundations that will support them for life. Over the past year, we’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on what that looks like for us at Orenda, what matters most, what actually sets children up for success, and what we can let go of.

What we’ve landed on is a strong, clear philosophy: if we’re going to teach literacy, we’re going to do it well. That means intentionality over speed, foundations over quick wins, and a deep respect for each child’s developmental journey.

We’re also in a really unique position to do this well because we are a multi-age group setting, and children don’t move through a series of rooms with different educators each year. Instead, many children are with us for four or five years, which allows us to start with strong baseline skills such as oral language and communication, and intentionally support their growth right across all the developmental areas they need before entering school. This continuity means learning can be built on over time, rather than feeling disjointed or reset each year.

Oral language and storytelling as the foundation of literacy

Before children ever pick up a pencil, language itself is the foundation. So much of literacy begins with rich oral language - conversations, storytelling, songs, and shared moments.

Storytelling is woven into our everyday life at Orenda. It happens through small world play, circle time, and the children’s own narratives (see our blog on storytelling). Over time, we’ve seen just how powerful this is. Some of our two-year-olds who have been with us since we opened have incredible vocabularies. When they tell stories, they use descriptive language, sequencing words, and layers of detail that bring their ideas to life.

This matters because language development and vocabulary are directly tied to literacy outcomes. When children can express their ideas clearly, describe, connect, and imagine, they’re already well on their way to becoming confident readers and writers. But it’s not just expressive language we’re nurturing, it’s also receptive language: learning to listen, follow stories, make predictions, and understand meaning.

A simple daily example of this is our circle-time story gatherings. Children often sit with props, retell familiar tales, or invent their own endings. We model rich vocabulary, but we also listen, giving children space to shape and own language.

We often notice that children who are reluctant to engage in drawing or writing are the very same children who can confidently narrate complex storylines in their play. They might not choose to sit at a table and make marks, but they can tell you exactly who each character is, what their job is, and what problem they are trying to solve. In many cases, their ideas and thinking are well ahead of their ability to represent them on paper.

While storytelling and conversation build rich language, children also need to learn how spoken words are made up of sounds. This is where phonological and phonemic awareness become so important.

Phonological and phonemic awareness.

If we had to name one of our biggest focuses in literacy, particularly with our pre-kinder and kinder children, , it would be phonological and phonemic awareness.

Phonological awareness is the broader skill, tuning into the larger sounds in language like words, syllables, and rhyme. We build this through playful, everyday moments:

Singing rhyming songs and pausing so children can fill in the missing word.

Playing “silly sentence” games with rhythm and alliteration.

Exploring syllables through circle time games using chants and clapping.

As children’s sound awareness deepens, we move to phonemic awareness, being able to hear and manipulate the smallest units of sound (phonemes). This is what underpins decoding and encoding.

Decoding is when children look at a word and break it into sounds to read it (for example, seeing cat and knowing it’s /c/ /a/ /t/).

Encoding is the reverse, when they want to write a word and can break it apart into sounds to spell it.

When we talk about letters and sounds, we also stay intentional with how we name them. We always connect the sound, the letter, and an anchor word, for example, “ a, apple /a/” or “m, moon, /m/.” This consistency helps children connect their growing sound awareness to written symbols when they’re ready to begin recognising letters.

At Orenda, we intentionally prioritise sound before symbol. One of the most effective ways we do this is through our after-rest literacy stations with our older children. These are short, playful, and responsive, a balance of explicit teaching and joyful exploration.

We spend a lot of time exploring these skills in stations, sometimes through reading rhyme-based picture books together, sometimes through games like SoundSnap, where we match rhyming picture cards. On other days, we might play a mystery box game, where children sort real objects by their initial sounds, for example, putting the paintbrush and pencil together, and the scissors and skeleton in another pile, blending their phonemic awareness skills with classifying and sorting skills.

It’s also important to note that stations are only a small part of our day. They usually involve three or four short rotations of around five minutes each, and only one of those stations may be directly focused on literacy. The others are often creative, fine motor, STEM, or pre-numeracy based. In total, this more targeted instructional time usually makes up about 15–20 minutes of a child’s whole day, with the rest of the day still rich in play, inquiry, storytelling, and creative exploration.

All of this playful sound work builds the foundation children need to make sense of print later. We can teach letter names at any time, but without this foundation, they’re just shapes. For some children, even when strong sound awareness and storytelling are in place, representing ideas on paper can still feel challenging.

When ideas outpace mark-making: Multiple ways to represent thinking.

For some children, particularly those who are deeply engaged in dramatic play and construction, mark-making can actually become a barrier to expressing what they know and think. Their ideas are complex, but their fine motor skills or confidence with drawing may not yet allow them to capture those ideas on paper.

Rather than seeing this as a problem to fix, we see it as a cue to widen the ways children can represent their thinking.

Alongside gentle and ongoing exposure to drawing and writing, we intentionally provide other avenues for children to communicate ideas, through loose parts, construction materials, small world play, and modelling with clay or paper clay. These experiences allow children to manipulate objects and use their imagination to stand in for people, places, and events.

This is an important step in symbolic thinking. When a rock becomes a house, or a stick becomes a character, children are learning that objects and symbols can represent ideas, which is essentially what writing is: symbols on paper representing thoughts.

A beautiful example of this has been our long-running “Dusty Gnomes” inquiry. This began after sharing a Steiner story with the children, which sparked a group of boys into creating their own dramatic play world outdoors. Their Dusty Gnome house became a large-scale construction using heavy rocks in the yard that they would lift, move, and redesign daily. This interest continued for many months and involved huge amounts of gross motor play, collaboration, and storytelling.

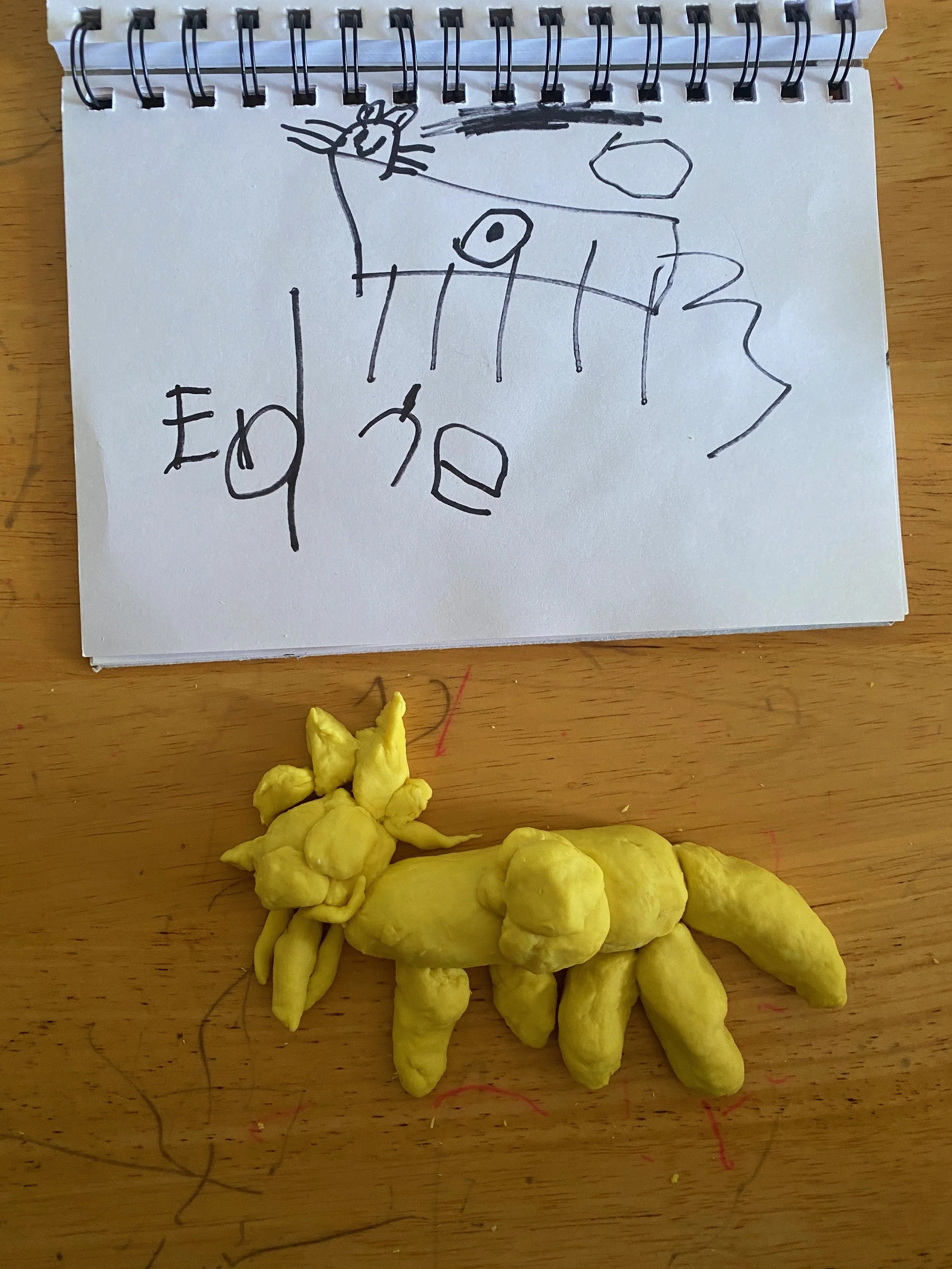

These were children who would rarely choose to draw independently. So we intentionally created moments, during stations, small group times, and circle discussions, where they could represent their Dusty Gnome house and characters through drawing, loose parts, and later through modelling with paper clay. What was fascinating was seeing how the same idea looked different each time: a simple sketch might show where the door was, a loose-parts construction might show how many rooms the house had, and a clay model might show walls and shelters that hadn’t appeared in drawings at all.

Each form of representation revealed different aspects of the children’s thinking and strengths. And importantly, because the work was connected to something they cared deeply about, their engagement with mark-making became purposeful rather than forced.

Alongside supporting children to represent their own ideas, we are also very intentional about how we model reading and print in everyday moments.

Modelling strong reading habits

Reading isn’t just about books, it’s about showing children how language works on a page. When we read, we will often model running our finger along the text, pointing to each word as we say it. This shows children that each written word corresponds to a spoken word.

We also model reading direction, left to right, top to bottom, and invite children to turn the pages, hold the book the right way up, and revisit favourite stories. These seemingly small behaviours build print awareness and book-handling skills, both of which are essential precursors to reading.

Another key part of this is comprehension. We don’t just read to children, we read with them. We pause to wonder together, make predictions, laugh at the funny parts, and talk about what might happen next. These small interactions grow the habits of active, engaged reading.

Why we teach lowercase first

One of the most practical but important choices we make is to teach lowercase letters first. When children bring home their first early readers from school, the majority of the text they’ll see is in lowercase. If they only know uppercase, the symbols on the page won’t mean anything to them.

When we write with children, whether it’s making a list together or scribing a child’s idea, we use lowercase. If a child asks how to write dog, we write dog, not DOG. Of course, we still model correct grammar in sentences, but lowercase is what they need to be most familiar with.

Many adults start with uppercase letters because they’re simpler to form, lots of straight lines, fewer curves. And while that may feel easier in the short term, it actually makes things harder later. Children have to “unlearn” and relearn. By starting with lowercase, we’re aligning what they see with what they’re learning, setting them up to make sense of words on a page right from the start.

Intentional use of fonts and letter modelling

Another small but important part of literacy teaching that often goes unnoticed is the fonts we use. When we type words for children, on labels, alphabet cards, or digital resources, we choose fonts that mirror the way letters are formed by hand.

Fonts that stylise letters (like the double-storey a or looped g) can be confusing for young learners, especially when they’re just beginning to match print to handwriting. If a printed g looks different from the one they’re practising, it becomes an unnecessary extra challenge for their developing visual memory.

At Orenda, we use a consistent and intentional set of alphabet cards across our environment, in our art space as small desk strips, and as larger cards children can use when writing. This helps create a cohesive visual language for letter learning. It means that when children look for support in forming a letter, the model they see is the same one they’ll use on paper.

When we model writing, we don’t just name the letter — we give the sound, the name, and the anchor word together: “We need an /o/... /o/ for ox,” or “Let’s add an /a/... /a/ for apple.”

We do this because it connects all parts of the literacy process:

The sound supports phonemic awareness.

The symbol connects that sound to print.

The anchor word gives it meaning and memory.

This level of consistency across the fonts we use, the language we model, and the tools children have access to helps make literacy learning smoother, clearer, and more meaningful.

Writing for real purposes: literacy in the everyday world

One of the most meaningful ways children begin to understand writing is when they see that words serve a purpose, that they help people, share information, and make the world work. Writing becomes real when it connects to their lived experiences.

At Orenda, we don’t set out to “teach writing” in isolation. Instead, we look for authentic opportunities for children to use writing as a tool for communication and contribution.

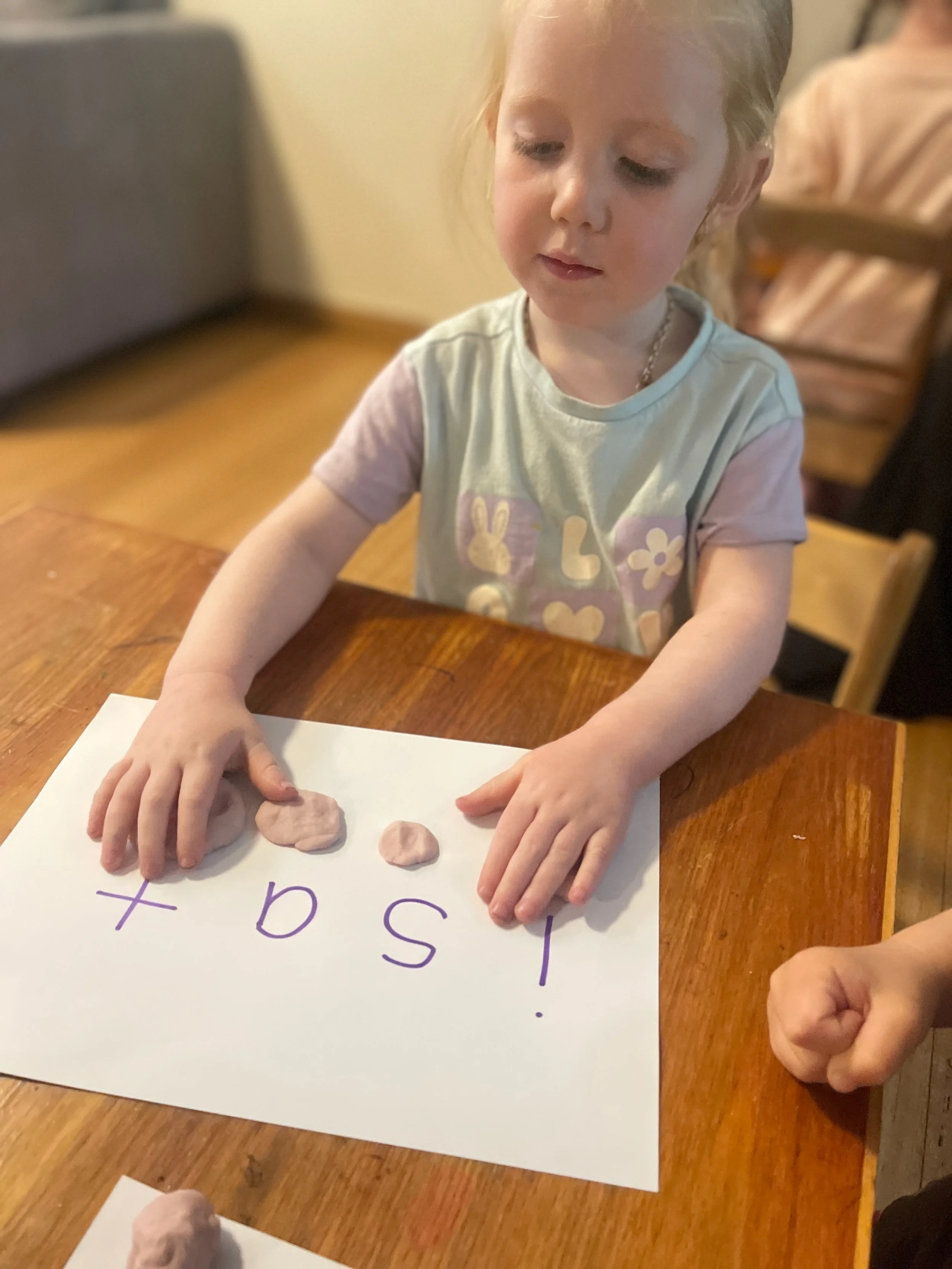

One example of this came through our museum inquiry, when the children decided to create signs to label their exhibits. For some of our younger children, we modelled letters on a whiteboard, and with that support, many could accurately write simple words, forming their letters correctly from top to bottom. For our older children, it became a chance to explore approximated (or inventive) spelling.

One child, for instance, wanted to write goat. He sounded it out and wrote g-o-t. We didn’t correct him, because at that stage, what mattered wasn’t spelling it “right,” but that he was applying his phonemic awareness, linking sounds to letters, and encoding language on his own.

This is a good example of working within a child’s Zone of Proximal Development, the place where learning is just challenging enough to stretch a child, but not so hard that it becomes frustrating. At this point, he could hear and record the sounds he knew, and that was exactly the right level of support for him. By focusing on what he could do, we help build confidence and skills that will naturally lead to more accurate spelling over time.

Another example came from our Friday group, who noticed that the postman was getting confused about where to deliver the mail, as our front door is blocked off and the entrance is around the back. The children decided to create a sign that read: “Orenda Circle, go around the right side.” They sounded out each word together, and the word circle was written with an “S,” a perfect example of inventive spelling informed by a child’s developing phonics knowledge.

These kinds of experiences show children that writing isn’t just something we do on paper, it’s how we share ideas, solve problems, and connect with others. And that’s the most powerful literacy lesson of all.

In summary

At Orenda, we believe early literacy isn’t about rushing children into reading and writing, it’s about building strong, intentional foundations. We nurture oral language through storytelling and conversation. We focus on phonological and phonemic awareness because it’s the bedrock of decoding and encoding. We model reading direction, support book handling, and grow comprehension through shared stories. We teach lowercase first, choose consistent fonts, and model letters with care. We bring uppercase in with purpose, surround children with meaningful print, and create authentic opportunities for writing. We respect developmental readiness, build motor foundations, and support approximated spelling in the ZPD.

This is literacy in action, woven through play, inquiry, and everyday life. We trust the process. We follow the child. And we make sure that what we’re teaching now is setting them up not just for success in school, but for a lifelong relationship with language.